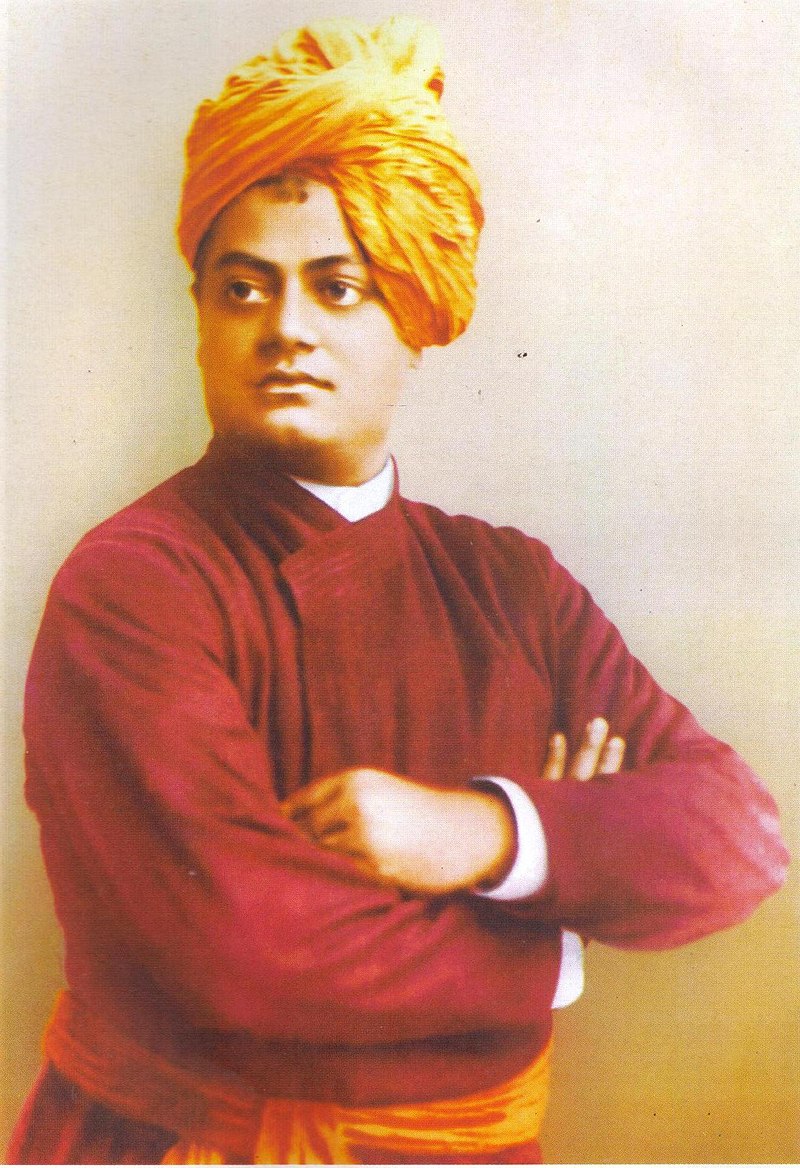

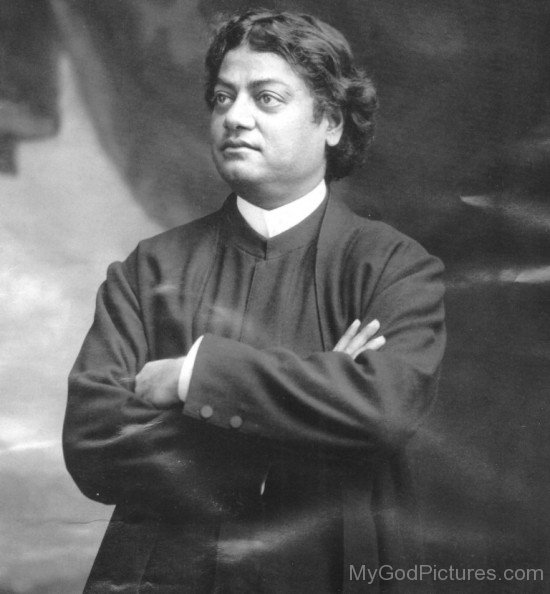

Swami Vivekananda was a Hindu monk from India. His teachings and philosophy are a reinterpretation and synthesis of various strands of Hindu thought, most notably classical yoga and (Advaita) Vedanta, with western esotericism and Universalism. He blended religion with nationalism, and applied this reinterpretation to various aspect’s of education, faith, character building as well as social issues pertaining to India. His influence extended also to the west, and he was instrumental in introducing Yoga to the west.

Advaita Vedanta

Main article: Neo-Vedanta

Influences

Vivekananda was influenced by the Brahmo Samaj and western Universalism and esotericism, and by his guru Ramakrishna, who regarded the Absolute and the relative reality to be nondual aspects of the same integral reality.

Western esoterism

While synthesizing and popularizing various strands of Hindu-thought, most notably classical yoga and (Advaita) Vedanta, Vivekananda was influenced by western ideas such as Universalism, via Unitarian missionaries who collaborated with the Brahmo Samaj. His initial beliefs were shaped by Brahmo concepts, which included belief in a formless God and the deprecation of idolatry, and a “streamlined, rationalized, monotheistic theology strongly coloured by a selective and modernistic reading of the Upanisads and of the Vedanta”. He propagated the idea that “the divine, the absolute, exists within all human beings regardless of social status”, and that “seeing the divine as the essence of others will promote love and social harmony”. Via his affiliations with Keshub Chandra Sen’s Nava Vidhan, the Freemasonry lodge, the Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, and Sen’s Band of Hope, Vivekananda became acquainted with Western esotericism.

Ramakrishna

In 1881 Narendra first met Ramakrishna, who became his spiritual focus after his own father had died in 1884. According to Banhatti, it was Ramakrishna who really answered Narendra’s question who had really seen God, by saying “Yes, I saw Him as I see you, only in an infinitely intenser sense.” Ramakrishna gradually brought Narendra to a Vedanta-based worldview that “provides the ontological basis for ‘śivajñāne jīver sevā’, the spiritual practice of serving human beings as actual manifestations of God.” According to Michael Taft, Ramakrishna reconciled the dualism of form and formless, regarding the Supreme Being to be both Personal and Impersonal, active and inactive. Ramakrishna stated that

The Personal and Impersonal are the same thing, like milk and its whiteness, the diamond and its lustre, the snake and its wriggling motion. It is impossible to conceive of the one without the other. The Divine Mother and Brahman are one.

Nevertheless, Vivekananda was more influenced by the Brahmo Samaj’s and its new ideas, than by Ramakrishna.

AdvaitaVedanta

Adhikārivāda in Hinduism, claimed special rights and privileges with regard to the right to universal knowledge of the Upanishads. Vivekananda rejected Adhikārivāda which, in his view, was the outcome of pure selfishness and ignored both the infinite possibilities of the human soul and the fact that all men are capable of receiving knowledge if it is imparted in their own respective languages. He claimed, there is no reason for access to the universal knowledge of the Upanishads to be restricted on the basis of caste or religion.

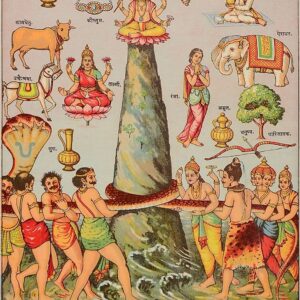

Vivekananda propagated that the essence of Hinduism was best expressed in Adi Shankara’s Advaita Vedanta philosophy. Nevertheless, following Ramakrishna, and in contrast to Advaita Vedanta, Vivekananda believed that the Absolute is both immanent and transcendent. According to Anil Sooklal, Vivekananda’s neo-Vedanta “reconciles Dvaita or dualism and Advaita or non-dualism,” viewing Brahman as “one without a second,” yet “both qualified, saguna, and qualityless, nirguna.” Vivekananda summarised the Vedanta as follows, giving it a modern and Universalistic interpretation, showing the influence of classical yoga:

Each soul is potentially divine. The goal is to manifest this Divinity within by controlling nature, external and internal. Do this either by work, or worship, or mental discipline, or philosophy — by one, or more, or all of these — and be free. This is the whole of religion. Doctrines, or dogmas, or rituals, or books, or temples, or forms, are but secondary details.

Yoga and Samkhya

Vivekananda’s emphasis on nirvikalpa samadhi was preceded by medieval yogic influences on Advaita Vedanta. In line with Advaita Vedanta texts like Dŗg-Dŗśya-Viveka (14th century) and Vedantasara (of Sadananda) (15th century), Vivekananda saw samadhi as a means to attain liberation.

Vivekananda popularized the notion of involution, a term which Vivekananda probably took from western Theosophists, notably Helena Blavatsky, in addition to Darwin’s notion of evolution, and possibly referring to the Samkhya term sātkarya. Theosophic ideas on involution has “much in common” with “theories of the descent of God in Gnosticism, Kabbalah, and other esoteric schools.” According to Meera Nanda, “Vivekananda uses the word involution exactly how it appears in Theosophy: the descent, or the involvement, of divine consciousness into matter.” With spirit, Vivekananda refers to prana or purusha, derived (“with some original twists”) from Samkhya and classical yoga as presented by Patanjali in the Yoga sutras.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet