Pongal , also referred to as Thai Pongal (தைப்பொங்கல்), is a multi-day Hindu harvest festival celebrated by Tamils. It is observed in the month of Thai according to the Tamil solar calendar and usually falls on 14 or 15 January. It is dedicated to the Surya, the Sun God and corresponds to Makar Sankranti, the harvest festival under many regional names celebrated throughout India.The three days of the Pongal festival are called Bhogi Pongal, Surya Pongal, and Mattu Pongal. Some Tamils celebrate a fourth day of Pongal known as Kanum Pongal.

According to tradition, the festival marks the end of winter solstice, and the start of the sun’s six-month-long journey northwards when the sun enters the Capricorn, also called as Uttarayana.The festival is named after the ceremonial “Pongal”, which means “to boil, overflow” and refers to the traditional dish prepared from the new harvest of rice boiled in milk with jaggery offered to Surya. Mattu Pongal is meant for celebration of cattle when the cattle are bathed, their horns polished and painted in bright colors, garlands of flowers placed around their necks and processions. It is traditionally an occasion for decorating rice-powder based kolam artworks, offering prayers in the home, temples, getting together with family and friends, and exchanging gifts to renew social bonds of solidarity.

Pongal is one of the most important festivals celebrated by Tamil people in Tamil Nadu and other parts of South India.It is also a major Tamil festival in Sri Lanka. It is observed by the Tamil diaspora worldwide, including those in Malaysia, Mauritius, South Africa, Singapore, United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and the Gulf countries.

Etymology

Thai Pongal is a portmanteau of two words: Thai (Tamil: ‘தை’) referring to the tenth month of the Tamil calendar and Pongal (from pongu) meaning “boiling over” or “overflow.” Pongal also refers to a sweet dish of rice boiled in milk and jaggery that is ritually prepared and consumed on the day.

History

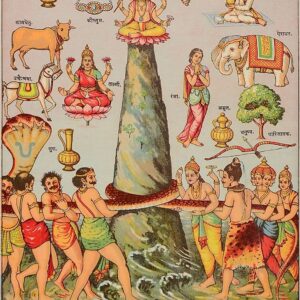

The principal theme of Pongal is thanking the Sun god Surya, the forces of nature and the farm animals and people who support agriculture. The festival is mentioned in an inscription in Viraraghava temple attributed to Chola king Kulottunga I (1070–1122 CE) which describes a grant of land to the temple for celebrating the annual Pongal festivities. The 9th-century Shiva bhakti text Thiruvembavai by Manikkavasagar vividly mentions the festival.

The history of the Pongal dish in festive and religious context can be traced to at least the Chola period. It appears in numerous texts and inscriptions with variant spellings. In early records, it appears as ponakam, tiruponakam, ponkal and similar terms. Temple inscriptions from Chola period to Vijayanagara period detail recipes similar to pongal recipes of the modern era with variations in seasonings and relative amounts of the ingredients. The terms ponakam, ponkal and its prefixed variants might also indicate the festive pongal dish as a prasadam which were given as a part of the meals served by free community kitchens in South Indian Hindu temples either as festival food or to pilgrims every day.

Pongal dish

Main article: Pongal (dish)

The festival’s most significant practice is the preparation of the traditional “pongal” dish. It utilizes freshly harvested rice, and is prepared by boiling it in milk and raw cane sugar (jaggery). Sometimes additional ingredients are added to the sweet dish, such as: cardamom, raisins, cashews and mung beans (split). Other ingredients include coconut and ghee (clarified butter from cow milk). Along with the sweet version of the Pongal dish, some prepare other versions such as salty and savoury (venpongal). According to Gutiérrez, women in some communities take their “cooking pots to the town center, or the main square, or near a temple of their choice or simply in front of their own home” and cook together as a social event. The cooking is done in sunlight, usually in a porch or courtyard, as the dish is dedicated to the Sun god, Surya. Relatives and friends are invited, and the standard greeting on the Pongal day typically is, “has the rice boiled”?

The cooking is done in a clay pot that is often garlanded with leaves or flowers, sometimes tied with a piece of turmeric root or marked with pattern artwork called kolam. It is either cooked at home, or in community gatherings such as in temples or village open spaces. It is the ritual dish, along with many other courses prepared from seasonal foods for all present. It is traditionally offered to the gods and goddesses first, followed sometimes by cows, then to friends and family gathered. Temples and communities organize free kitchen prepared by volunteers to all those who gather. According to Andre Bateille, this tradition is a means to renew social bonds. Portions of the sweet pongal dish (sakkara pongal) are distributed as the prasadam in Hindu temples.

The dish and the process of its preparation is a part of the symbolism, both conceptually and materially. It celebrates the harvest, the cooking transforms the gift of agriculture into nourishment for the gods and the community on a day that Tamil’s traditionally believe marks the end of winter solstice and starts the sun god’s journey north. The blessing of abundance by Goddess Pongal (Uma, Parvati) is symbolically marked by the dish “boiling over”.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet