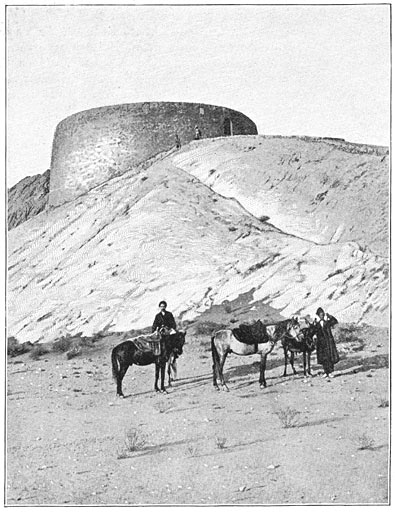

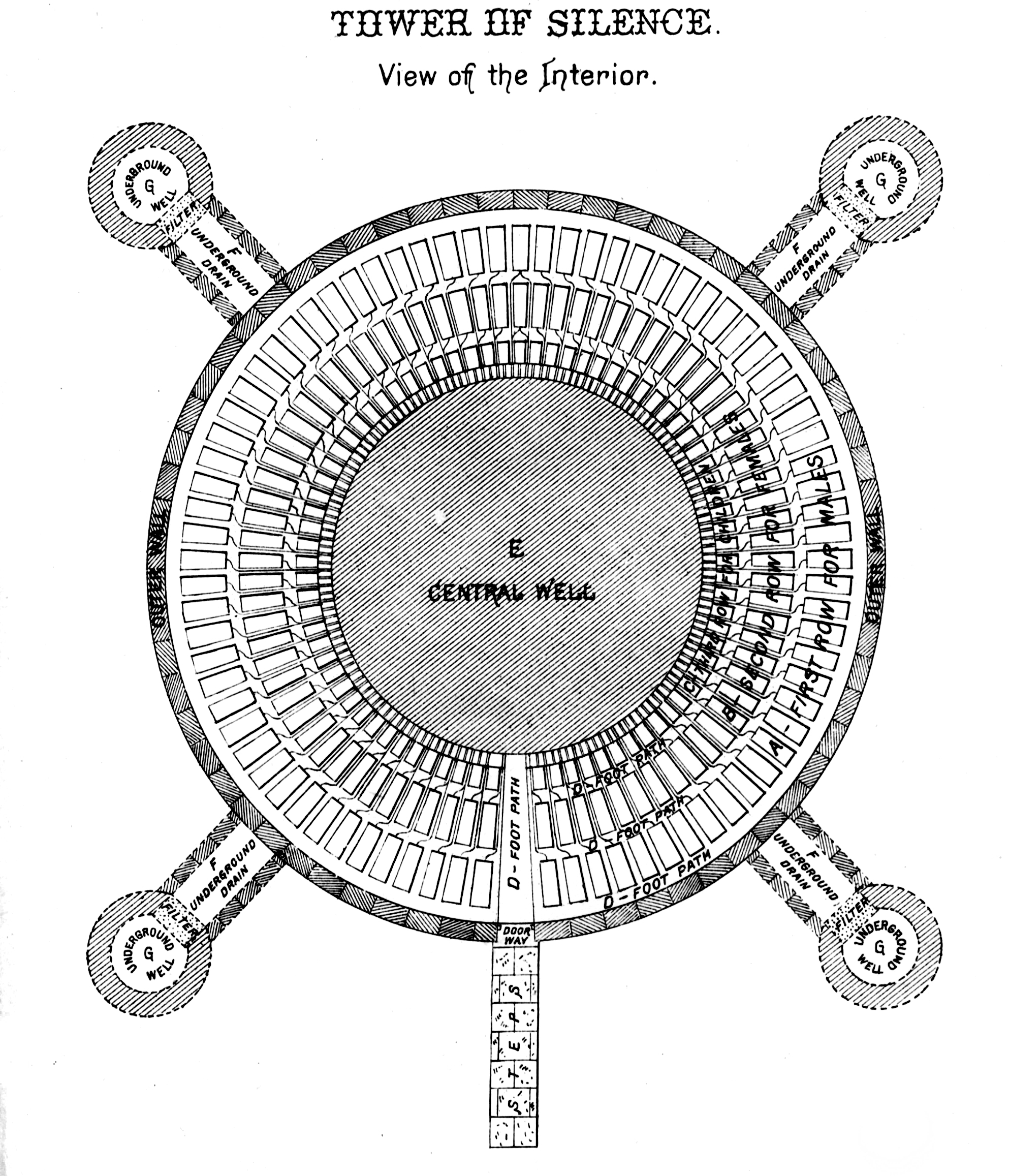

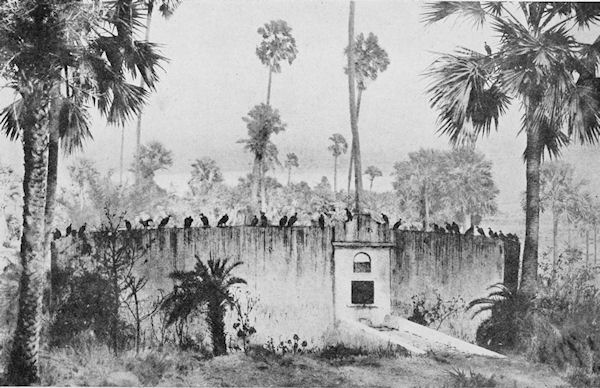

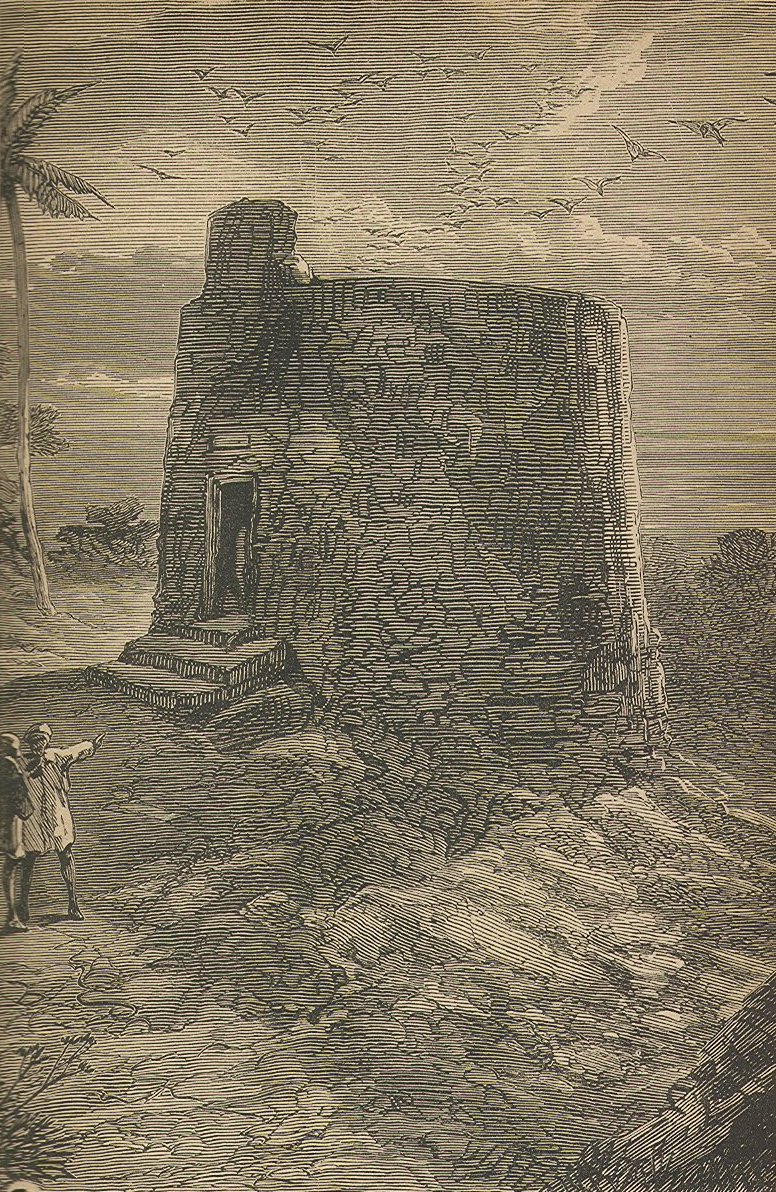

A dakhma (Persian: دخمه), otherwise referred to as Tower of Silence (Persian: برجِ خاموشان), is a circular, raised structure built by Zoroastrians for excarnation (that is, the exposure of human corpses to the elements with the purpose to enable their decomposition), in order to avoid contamination of the soil and other natural elements by the decomposing dead bodies. Carrion birds, usually vultures and other scavengers, consume the flesh. Skeletal remains are gathered into a central pit where further weathering and continued breakdown occurs.

Ritual exposure by Iranian peoples

Main articles: Ancient Persia and Zoroastrians in Iran

Zoroastrian ritual exposure of the dead is first attested in the mid-5th century BCE Histories of Herodotus, an Ancient Greek historian who observed the custom amongst Iranian expatriates in Asia Minor; however, the use of towers is first documented in the early 9th century CE. In Herodotus’ account (in Histories i.140), the Zoroastrian funerary rites are said to have been “secret”; however they were first performed after the body had been dragged around by a bird or dog. The corpse was then embalmed with wax and laid in a trench.

Writing on the culture of the Persians, Herodotus reports on the Persian burial customs performed by the magi, again, kept secret, according to his account. However, he writes that he knows they expose the body of male dead to dogs and birds of prey, then they cover the corpse in wax, and then it is buried. The Achaemenid custom for the dead is recorded in the regions of Bactria, Sogdia, and Hyrcania, but not in Western Iran.

The discovery of ossuaries in both Eastern and Western Iran dating to the 5th and 4th centuries BCE indicate that bones were sometimes isolated, but separation occurring through ritual exposure cannot be assumed: burial mounds, where the bodies were wrapped in wax, have also been discovered. The tombs of the Achaemenid emperors at Naqsh-e Rustam and Pasargadae likewise suggest non-exposure, at least until the bones could be collected. According to legend (incorporated by Ferdowsi into his Shahnameh; lit. ’The Book of Kings’), Zoroaster himself is interred in a tomb at Balkh (in present-day Afghanistan).

The Byzantine historian Agathias has described the Zoroastrian burial of the Sasanian general Mihr-Mihroe: “the attendants of Mermeroes took up his body and removed it to a place outside the city and laid it there as it was, alone and uncovered according to their traditional custom, as refuse for dogs and horrible carrion”.

Towers are a much later invention and are first documented in the early 9th century CE. The funerary ritual customs surrounding that practice appear to date to the Sassanid era (3rd–7th CE). They are known in detail from the supplement to the Shayest ne Shayest, the two Rivayat collections, and the two Saddars.

One of the earliest literary descriptions of such a building appears in the late 9th-century Epistles of Manushchihr, where the technical term is astodan, ‘ossuary’. Another term that appears in the 9th- to 10th-century texts of Zoroastrian tradition (the so-called “Pahlavi books”) is dakhmag; in its earliest usage, it referred to any place for the dead.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet