Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is a terrestrial planet and is the closest in mass and size to its orbital neighbour Earth. Venus is notable for having the densest atmosphere of the terrestrial planets, composed mostly of carbon dioxide with a thick, global sulfuric acid cloud cover. At the surface it has a mean temperature of 737 K (464 °C; 867 °F) and a pressure of 92 times that of Earth’s at sea level. These extreme conditions compress carbon dioxide into a supercritical state close to Venus’s surface.

Internally, Venus has a core, mantle, and crust. Venus lacks an internal dynamo, and its weakly induced magnetosphere is caused by atmospheric interactions with the solar wind. Internal heat escapes through active volcanism, resulting in resurfacing instead of plate tectonics. Venus is one of two planets in the Solar System, the other being Mercury, that have no moons. Conditions perhaps favourable for life on Venus have been identified at its cloud layers. Venus may have had liquid surface water early in its history with a habitable environment, before a runaway greenhouse effect evaporated any water and turned Venus into its present state.

The rotation of Venus has been slowed and turned against its orbital direction (retrograde) by the currents and drag of its atmosphere. It takes 224.7 Earth days for Venus to complete an orbit around the Sun, and a Venusian solar year is just under two Venusian days long. The orbits of Venus and Earth are the closest between any two Solar System planets, approaching each other in synodic periods of 1.6 years. Venus and Earth have the lowest difference in gravitational potential of any pair of Solar System planets. This allows Venus to be the most accessible destination and a useful gravity assist waypoint for interplanetary flights from Earth.

Venus figures prominently in human culture and in the history of astronomy. Orbiting inferiorly (inside of Earth’s orbit), it always appears close to the Sun in Earth’s sky, as either a “morning star” or an “evening star”. While this is also true for Mercury, Venus appears more prominent, since it is the third brightest object in Earth’s sky after the Moon and the Sun. In 1961, Venus became the target of the first interplanetary flight, Venera 1, followed by many essential interplanetary firsts, such as the first soft landing on another planet by Venera 7 in 1970. These probes demonstrated the extreme surface conditions, an insight that has informed predictions about global warming on Earth. This finding ended the theories and then popular science fiction about Venus being a habitable or inhabited planet.

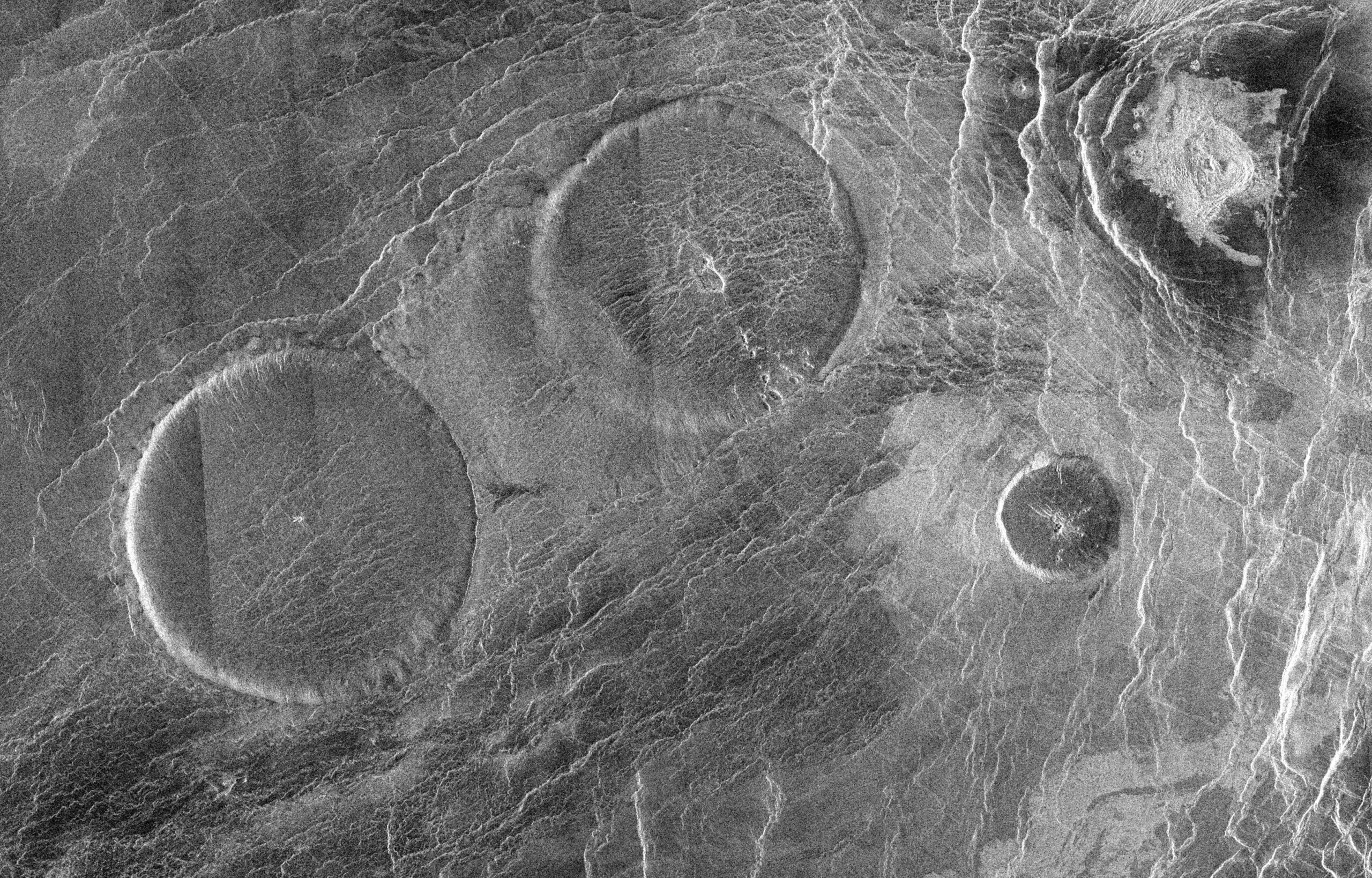

The Venusian surface was a subject of speculation until some of its secrets were revealed by planetary science in the 20th century. Venera landers in 1975 and 1982 returned images of a surface covered in sediment and relatively angular rocks. The surface was mapped in detail by Magellan in 1990–91. The ground shows evidence of extensive volcanism, and the sulphur in the atmosphere may indicate that there have been recent eruptions.

About 80% of the Venusian surface is covered by smooth, volcanic plains, consisting of 70% plains with wrinkle ridges and 10% smooth or lobate plains. Two highland “continents” make up the rest of its surface area, one lying in the planet’s northern hemisphere and the other just south of the equator. The northern continent is called Ishtar Terra after Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of love, and is about the size of Australia. Maxwell Montes, the highest mountain on Venus, lies on Ishtar Terra. Its peak is 11 km (7 mi) above the Venusian average surface elevation. The southern continent is called Aphrodite Terra, after the Greek mythological goddess of love, and is the larger of the two highland regions at roughly the size of South America. A network of fractures and faults covers much of this area.

There is recent evidence of lava flow on Venus (2024), such as flows on Sif Mons, a shield volcano, and on Niobe Planitia, a flat plain. There are visible calderas. The planet has few impact craters, demonstrating that the surface is relatively young, at 300–600 million years old. Venus has some unique surface features in addition to the impact craters, mountains, and valleys commonly found on rocky planets. Among these are flat-topped volcanic features called “farra”, which look somewhat like pancakes and range in size from 20 to 50 km (12 to 31 mi) across, and from 100 to 1,000 m (330 to 3,280 ft) high; radial, star-like fracture systems called “novae”; features with both radial and concentric fractures resembling spider webs, known as “arachnoids”; and “coronae”, circular rings of fractures sometimes surrounded by a depression. These features are volcanic in origin.

Surface panorama taken by Venera 13

Most Venusian surface features are named after historical and mythological women. Exceptions are Maxwell Montes, named after James Clerk Maxwell, and highland regions Alpha Regio, Beta Regio, and Ovda Regio. The last three features were named before the current system was adopted by the International Astronomical Union, the body which oversees planetary nomenclature.

The longitude of physical features on Venus is expressed relative to its prime meridian. The original prime meridian passed through the radar-bright spot at the centre of the oval feature Eve, located south of Alpha Regio. After the Venera missions were completed, the prime meridian was redefined to pass through the central peak in the crater Ariadne on Sedna Planitia.

The stratigraphically oldest tessera terrains have consistently lower thermal emissivity than the surrounding basaltic plains measured by Venus Express and Magellan, indicating a different, possibly a more felsic, mineral assemblage. The mechanism to generate a large amount of felsic crust usually requires the presence of water ocean and plate tectonics, implying that habitable condition had existed on early Venus with large bodies of water at some point. However, the nature of tessera terrains is far from certain.

Studies reported on 26 October 2023 suggest for the first time that Venus may have had plate tectonics during ancient times and, as a result, may have had a more habitable environment, possibly one capable of sustaining life. Venus has gained interest as a case for research into the development of Earth-like planets and their habitability.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet