Yoga ( Sanskrit: योग, lit. ’yoke’ ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-consciousness untouched by the mind (Chitta) and mundane suffering (Duḥkha). There is a wide variety of schools of yoga, practices, and goals in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, and traditional and modern yoga is practiced worldwide.

Yoga-like practices were first mentioned in the ancient Hindu text known as Rigveda. Yoga is referred to in a number of the Upanishads. The first known appearance of the word “yoga” with the same meaning as the modern term is in the Katha Upanishad, which was probably composed between the fifth and third centuries BCE. Yoga continued to develop as a systematic study and practice during the fifth and sixth centuries BCE in ancient India’s ascetic and Śramaṇa movements.The most comprehensive text on Yoga, the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, date to the early centuries of the Common Era; Yoga philosophy became known as one of the six orthodox philosophical schools (Darśanas) of Hinduism in the second half of the first millennium CE.Hatha yoga texts began to emerge between the ninth and 11th centuries, originating in tantra.

Two general theories exist on the origins of yoga. The linear model holds that yoga originated in the Vedic period, as reflected in the Vedic textual corpus, and influenced Buddhism; according to author Edward Fitzpatrick Crangle, this model is mainly supported by Hindu scholars. According to the synthesis model, yoga is a synthesis of non-Vedic and Vedic elements; this model is favoured in Western scholarship.

The term “yoga” in the Western world often denotes a modern form of Hatha yoga and a posture-based physical fitness, stress-relief and relaxation technique, consisting largely of asanas; this differs from traditional yoga, which focuses on meditation and release from worldly attachments. It was introduced by gurus from India after the success of Swami Vivekananda’s adaptation of yoga without asanas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Vivekananda introduced the Yoga Sutras to the West, and they became prominent after the 20th-century success of hatha yoga.

Etymology

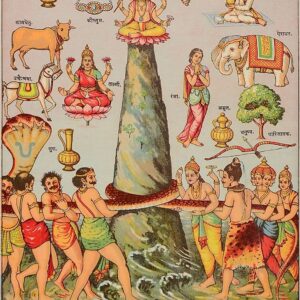

Outdoor statue

A statue of Patanjali, author of the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, meditating in the lotus position

The Sanskrit noun योग yoga is derived from the root yuj (युज्) “to attach, join, harness, yoke”. Yoga is a cognate of the English word “yoke”. According to Mikel Burley, the first use of the root of the word “yoga” the Rigveda, a dedication to the rising Sun-god, where it has been interpreted as “yoke” or “control”.

Pāṇini (4th c. BCE) wrote that the term yoga can be derived from either of two roots: yujir yoga (to yoke) or yuj samādhau (“to concentrate”). In the context of the Yoga Sutras, the root yuj samādhau (to concentrate) is considered the correct etymology by traditional commentators.

In accordance with Pāṇini, Vyasa (who wrote the first commentary on the Yoga Sutras) says that yoga means samadhi (concentration). In the Yoga Sutras , kriyāyoga is yoga’s “practical” aspect: the “union with the supreme” in the performance of everyday duties. A person who practices yoga, or follows the yoga philosophy with a high level of commitment, is called a yogi; a female yogi may also be known as a yogini.

Definitions in classical texts

The term “yoga” has been defined in different ways in Indian philosophical and religious traditions.

| Source Text | Approx. Date | Definition of Yoga |

| Vaisesika sutra | c. 4th century BCE | “Pleasure and suffering arise as a result of the drawing together of the sense organs, the mind and objects. When that does not happen because the mind is in the self, there is no pleasure or suffering for one who is embodied. That is yoga” |

| Katha Upanishad | last centuries BCE | “When the five senses, along with the mind, remain still and the intellect is not active, that is known as the highest state. They consider yoga to be firm restraint of the senses. Then one becomes un-distracted for yoga is the arising and the passing away” |

| Bhagavad Gita | c. 2nd century BCE | “Be equal minded in both success and failure. Such equanimity is called Yoga” |

| “Yoga is skill in action” “Know that which is called yoga to be separation from contact with suffering” | ||

| Yoga Sutras of Patanjali | c. first centuries CE[16][43][note 1] | 1.2. yogas chitta vritti nirodhah – “Yoga is the calming down the fluctuations/patterns of mind” |

| 1.3. Then the Seer is established in his own essential and fundamental nature. | ||

| 1.4. In other states there is assimilation (of the Seer) with the modifications (of the mind). | ||

| Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra (Sravakabhumi), a Mahayana Buddhist Yogacara work | 4th century CE | “Yoga is fourfold: faith, aspiration, perseverance and means” |

| Kaundinya’s Pancarthabhasya on the Pashupata-sutra | 4th century CE | “In this system, yoga is the union of the self and the Lord” |

| Yogaśataka a Jain work by Haribhadra Suri | 6th century CE | “With conviction, the lords of Yogins have in our doctrine defined yoga as the concurrence (sambandhah) of the three [correct knowledge (sajjñana), correct doctrine (saddarsana) and correct conduct (saccaritra)] beginning with correct knowledge, since [thereby arises] conjunction with liberation….In common usage this [term] yoga also [denotes the Self’s] contact with the causes of these [three], due to the common usage of the cause for the effect.” |

| Linga Purana | 7th–10th century CE | “By the word ‘yoga’ is meant nirvana, the condition of Shiva.” |

| Brahmasutra-bhasya of Adi Shankara | c. 8th century CE | “It is said in the treatises on yoga: ‘Yoga is the means of perceiving reality’ (atha tattvadarsanabhyupāyo yogah)” |

| Mālinīvijayottara Tantra, one of the primary authorities in non-dual Kashmir Shaivism | 6th–10th century CE | “Yoga is said to be the oneness of one entity with another.” |

| Mrgendratantravrtti, of the Shaiva Siddhanta scholar Narayanakantha | 6th–10th century CE | “To have self-mastery is to be a Yogin. The term Yogin means “one who is necessarily “conjoined with” the manifestation of his nature…the Siva-state (sivatvam)” |

| Śaradatilaka of Lakshmanadesikendra, a Shakta Tantra work | 11th century CE | “Yogic experts state that yoga is the oneness of the individual Self (jiva) with the atman. Others understand it to be the ascertainment of Siva and the Self as non-different. The scholars of the Agamas say that it is a Knowledge which is of the nature of Siva’s Power. Other scholars say it is the knowledge of the primordial Self.” |

| Yogabija, a Hatha yoga work | 14th century CE | “The union of apana and prana, one’s own rajas and semen, the sun and moon, the individual Self and the supreme Self, and in the same way the union of all dualities, is called yoga. “ |

Goals

The ultimate goals of yoga are stilling the mind and gaining insight, resting in detached awareness, and liberation (Moksha) from saṃsāra and duḥkha: a process (or discipline) leading to unity (Aikyam) with the divine (Brahman) or with one’s self (Ātman). This goal varies by philosophical or theological system. In the classical Astanga yoga system, the ultimate goal of yoga is to achieve samadhi and remain in that state as pure awareness.

According to Knut A. Jacobsen, yoga has five principal meanings:

A disciplined method for attaining a goal

Techniques of controlling the body and mind

A name of a school or system of philosophy (darśana)

With prefixes such as “hatha-, mantra-, and laya-, traditions specialising in particular yoga techniques

The goal of Yoga practice

David Gordon White writes that yoga’s core principles were more or less in place in the 5th century CE, and variations of the principles developed over time:

A meditative means of discovering dysfunctional perception and cognition, as well as overcoming it to release any suffering, find inner peace, and salvation. Illustration of this principle is found in Hindu texts such as the Bhagavad Gita and Yogasutras, in a number of Buddhist Mahāyāna works, as well as Jain texts.

The raising and expansion of consciousness from oneself to being coextensive with everyone and everything. These are discussed in sources such as in Hinduism Vedic literature and its epic Mahābhārata, the Jain Praśamaratiprakarana, and Buddhist Nikaya texts.

A path to omniscience and enlightened consciousness enabling one to comprehend the impermanent (illusive, delusive) and permanent (true, transcendent) reality. Examples of this are found in Hinduism Nyaya and Vaisesika school texts as well as Buddhism Mādhyamaka texts, but in different ways.

A technique for entering into other bodies, generating multiple bodies, and the attainment of other supernatural accomplishments. These are, states White, described in Tantric literature of Hinduism and Buddhism, as well as the Buddhist Sāmaññaphalasutta. James Mallinson, however, disagrees and suggests that such fringe practices are far removed from the mainstream Yoga’s goal as meditation-driven means to liberation in Indian religions.

According to White, the last principle relates to legendary goals of yoga practice; it differs from yoga’s practical goals in South Asian thought and practice since the beginning of the Common Era in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain philosophical schools.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet